October 2019 Mission: Patient Update

Meet Wideline

Even in the best of times, the trip from Eliana Sainvil’s village to Port-au-Prince takes a day of hard driving over bad roads. But when her rattletrap taxi rounded a bend to encounter a smoldering roadblock of burning tires, Eliana knew her journey was about to become much harder, and more dangerous.

Under a sudden hail of protestors’ thrown rocks, her driver braked hard, shoved the car into reverse, and retreated up the road. But for Eliana, who was traveling with her gravely ill 15-year-old daughter Wideline, waiting until the road reopened wasn’t an option. If they didn’t make it to Port-au-Prince within 24 hours, they would miss their ride to the Dominican Republic for Wideline’s emergency heart surgery.

We’re getting out, Eliana told the driver.

A few minutes later, with one arm supporting Wideline and the other steadying a suitcase atop her head, Eliana began helping her daughter through the plumes of acrid smoke, ducking the occasional rock and hoping that nearby gunfire didn’t get any closer.

“I was very, very afraid,” Wideline said.

Given Haiti’s widespread civil unrest – a reaction to endemic corruption and gross inequality – Eliana felt she couldn’t trust anyone. Only her faith and the three dollars she had pocketed from selling the last of her goats would see them through to safety. “All I kept thinking about,” Eliana said, “was that, when the doctors would see Wideline, they’d be able to take care of her.”

After several of hours limping down the road, Eliana flagged down a passing driver who demanded the last of her money to ferry them to their rendezvous in Port-au-Prince. There, a social worker from the Haiti Cardiac Alliance – a nonprofit that works to match young Haitians suffering cardiac problems with appropriate medical care abroad – packed them into a battered van with four other patients, their parents and with two armed guards, for the first leg of their 200-mile trip to the Dominican capital of Santo Domingo.

Wideline’s journey had been a long one in more ways than one. Doctors had actually diagnosed her rheumatic heart disease five years earlier, but the Haiti Cardiac Alliance has a rolling waiting list of more than 400 indigent patients. This, coupled with the challenge of matching Wideline with a qualified surgical team abroad, had meant years of delay, even as her condition deteriorated. With time running out, her surgery was now or never.

“The general state of health infrastructure in Haiti is poor,” said Owen Robinson, Executive Director of the Haiti Cardiac Alliance. “It’s never been at a sufficient level, especially in a specialty like cardiology. There’s a lack of training, a lack of hospital beds, and supply chain problems in terms of getting medicine. And then there’s the bureaucracy of passports and visas. We have one or two patients die a week, just waiting.”

Fortunately, on this particular day, the trip to Santo Domingo went smoothly – including the border crossing, which each patient had to make on the back of a roaring motorbike.

Two days later, Wideline lay on a gurney in Santo Domingo’s CEDIMAT hospital, waiting for her turn in the operating room. Paradoxically, the most dangerous part of her odyssey was about to begin: the surgery itself.

Over the next six hours, doctors would cut open her chest, reroute her blood through a heart-lung machine, stop her heart from beating, repair or replace multiple valves, zap the heart back into action, and then sew her shut again – all while preventing any number of possible complications or deadly infections. For an adult, this is hard surgery. For a sick child, it’s exceptionally risky.

Fortunately, the surgeon leading Wideline’s operation was Dr. David Adams, President of the Mitral Foundation and Cardiac Surgeon-in-Chief at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York, and one of the top mitral valve surgeons in the world.

But even Dr. Adams, along with CEDIMAT’s chief pediatric surgeon, Dr. Juan Leon, were shocked by what they discovered when the surgical team actually opened her chest: heart anatomy so distorted by disease that in thousands of heart surgeries, they had never seen anything like it.

“Nobody in her condition makes it this long,” Dr. Adams said. “She’s at the very end of her compensatory curve, and is truly dying from her valve disease. So the pressure’s really on today. There’s no gimme here.”

Such difficult cases, of course, were the reason Dr. Adams and his team had flown more 1,500 miles from New York on this medical mission – to tackle exceptionally complex repairs that most surgeons would deem impossible, let alone perform free of charge on children with a high risk of mortality.

“There are only a few cardiac surgeons in the world who can do this successfully,” Dr. Adams said. “That’s why it’s so critical that we not just save these sick kids, but also train more surgeons in advanced repair techniques.” This is especially in the Caribbean, a region with a high incidence of rheumatic fever and generally poor medical infrastructure.

Dr. Adams and Dr. Leon, collaborating with a combined team of about 20, worked nonstop to give Wideline a second chance at life – step by step, cut by cut, suture by suture. For the young girl, anesthetized and sustained on the very edge of life and death, any surgical mistake could prove fatal.

In the operating room, every minute is important, because the longer a patient remains under anesthesia and the more time their blood must being oxygenated and pumped by the bypass machine, the greater the risk that they will suffer life-threatening complications. Despite this urgency, doctors can’t afford to rush, because such complex procedures demand the utmost precision.

“It doesn’t matter if you’ve done a procedure 10,000 times – you have to get it exactly right, today,” Dr. Adams said. “And in a child’s heart, you have to be especially careful. Just a millimeter’s difference can make the difference.”

As the hours passed and Wideline’s surgery progressed, the mood in the operating room slowly shifted. The tense silence of early concentration slowly gave way to a murmur of relaxed conversation. The beeps and whir of the life support machines were joined by crooning country music from Dr. Adams’ iPhone. Meanwhile, talk about Wideline turned from survival to recovery, and how the team could transform head-cam footage of the operation into training video.

“Given her condition, she showed unbelievable heart,” Dr. Adams said, afterward “She’s going to be fine.” Indeed, the very next day, with support from her mother on one side and a nurse on the other, Wideline actually took a slow walk around the intensive care unit.

Still weak but smiling widely when Dr. Adams stopped by her bedside to check in, Wideline thanked him for saving her. So did her mom. “God is in the first position, but doctors are in the second position,” Eliana said. “I am so happy she got the surgery, and that the doctors knew what they were doing.”

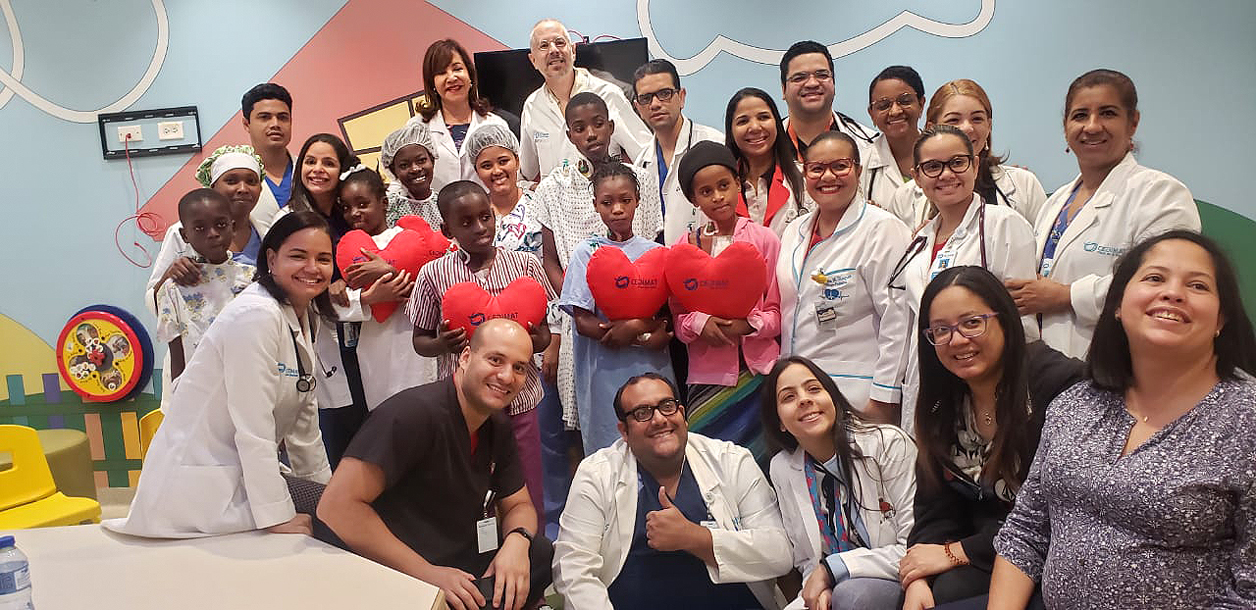

Within a week, if all went well on the return journey, Wideline would be back at home and, within a few weeks, back in school for the first time in a year. The rest of her fellow patients –including six from Haiti and two from the Dominican Republic – were also up and walking within a day of surgery, and due to leave the hospital within 72 hours.

“These kids were sick for many years,” Dr. Leon said. “It’s so great to see them after surgery, coming back to life.”

Collectively, these operations – conducted over two days – marked the third round of surgery for the Children’s Valve Project, which aims to fix 100 children’s hearts in the next several years, all while honing local surgical expertise in valve repair.

As Dr. Leon notes, valve repair takes time to master. “Because every patient is different, it’s not something you can learn in just a couple of surgeries,” he said. But “working beside Dr. Adams, you get so much information that you can’t get from books, or see in videos. He will explain every single step, point out the different formations, and how to read and successfully repair the valve.”

Dr. Adams and the Children’s Valve Project are already planning the next round of surgeries at CEDIMAT, with support from Every Heartbeat Matters – a philanthropic initiative led by Edwards Lifesciences to educate, screen and treat 1.5 million underserved people fighting heart valve disease around the world, the Haiti Cardiac Alliance, the David Ortiz Children’s Fund, the Mount Sinai Health System, the Mitral Foundation, and individual donors.

“Just look at these kids. We’re making a difference,” Dr. Adams said. “This is God’s work.”